by Sarah Halter

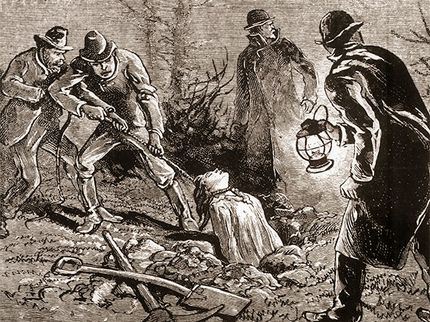

July 6, 2021 Update: If you missed our May 23, 2021 virtual program on “Medical Education and Body Snatching in Indiana,” never fear! The recording is now available here. One famous incident I mentioned during the program has sometimes been referred to as The Harrison Horror. The story was too long to tell in full, but as promised, here are the fascinating details. [Image: print of body snatchers at work, Library of Congress]

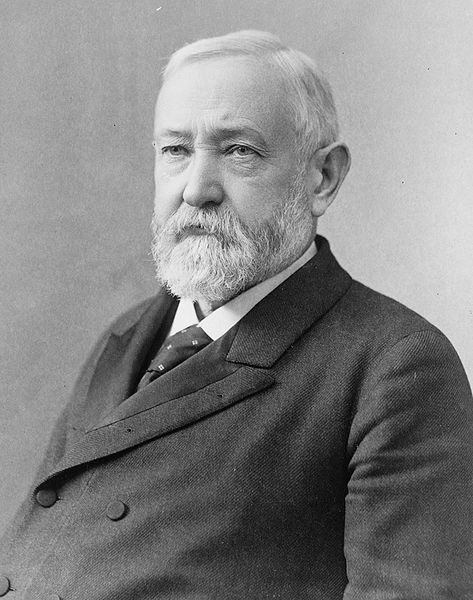

In the early spring of 1878, General Benjamin Harrison visited his father at his home in Point Farm, Ohio, a suburb of Cincinnati. (He was still General Harrison, because he hadn't become the President of the United States yet. That didn't happen until 1889. Learn more about President Harrison from the Benjamin Harrison Presidential Site here.)

During that visit, John Scott Harrison was in pretty good health, so when he died on May 26th, it was a bit of a shock despite his age. Just the week before, in fact, General Harrison received a letter that his father had ridden 12 miles on horseback to attend the funeral service and burial of a distant nephew, a young man named Augustus Devin, who had died unexpectedly at just 23 years old. But on that Sunday morning, May 26, 1878, when General Harrison and his family came back home from church a waiting telegram informed him that his father had passed away in the night. Right away General Harrison and his wife, Caroline, got on a train and headed down to be with his family and lay his father to rest. [Image: photo of President Benjamin Harrison, 1896, Library of Congress]

The old family mansion was suddenly a bustling place. Hundreds of people came to offer condolences to the Harrison family. They began making plans to bury John Scott Harrison at Congress Green Cemetery, near where Augustus Devin had been buried just the previous week. While visiting the cemetery before the funeral, family members noticed that there was something odd about Augustus' grave. It looked like it had been disturbed. When they got a closer look, to everyone's shock and horror, it was clear that the grave had been robbed… Augustus' body had been stolen.

If someone stole Augustus' body right out of his grave, might someone do the same to John Scott Harrison's body? This was the beloved patriarch of the family and the last son of William Henry Harrison, the US President who famously died a month into his presidency. His body and his grave had to be protected at any cost, and the Harrison family could afford to pay for it.

---

On May 29th, the vast funeral procession proceeded to Congress Green Cemetery. General Harrison himself supervised the lowering of the sturdy and secure metal casket that contained John Scott Harrison's body into the freshly dug grave. The grave was eight feet deep, and at the bottom was a brick vault into which the casket was placed. The walls of the vault were thick, and the bottom was lined with a stone floor. Workmen placed three massive stones on top of the vault, two at the foot end of the casket and one extra large stone at the head of the casket, where body snatchers usually struck. But they didn't stop there. Next the stones were cemented together, and then several men stood watch at the open grave for several hours while the cement dried. Then finally, the rest of the hole on top of the stones was filled in with dirt. General Harrison, fearful that the body snatchers would return, paid a watchman $30 to stand guard over the grave for 30 nights until the body decomposed enough to make it useless for dissection.

---

General Harrison and his wife returned to Indianapolis after the funeral feeling pretty confident, I imagine, that his father's body was safe. He went on about his business as one of the City's most well-known lawyers. His brother John stayed in Cincinnati the night of the funeral, so that bright and early the next morning, he could begin the search for the missing body of Augustus Devin.

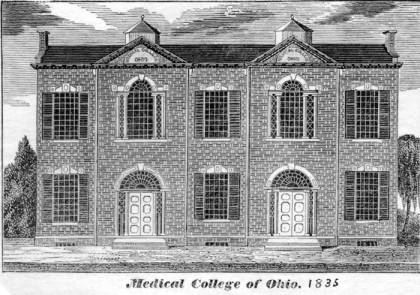

John Harrison and a constable named Lacey set out to search all of the medical schools in the area. They got a tip that a wagon was seen pulling up in the alley behind the Ohio Medical College building at 3am the previous night. A large object was removed from the wagon and carried into the college building, and then the wagon drove on. It was a promising lead. And so, they began the search there. [Image: Ohio Medical College, 1835, The Ohio History Connection]

John Harrison and a constable named Lacey set out to search all of the medical schools in the area. They got a tip that a wagon was seen pulling up in the alley behind the Ohio Medical College building at 3am the previous night. A large object was removed from the wagon and carried into the college building, and then the wagon drove on. It was a promising lead. And so, they began the search there. [Image: Ohio Medical College, 1835, The Ohio History Connection]

When they arrived, the irritated janitor reluctantly showed them around the building, taking them from room to room, so that they could see for themselves that there were no illegal bodies at the Ohio Medical College.

After John and the constable had carefully searched the whole building without finding anything suspicious, they were about to leave when Constable Lacey noticed an odd thing. He saw a oddly placed air vent with a windlass. The windlass had a rope tied to it that hung down into the air shaft. And the rope looked tight, like something heavy might be hanging from it. They ordered the janitor to pull it up. And as the rope was pulled up, slowly a figure began to emerge. It was a body with a rope tied around its neck. But was it Augustus Devin? Was their search over already in the first place they tried?

It was not.

The head and shoulders were covered with a cloth, but John Harrison could tell by looking at the rest of the naked body that it was a much older man than Augustus Devin was. But whether it was Augustus or not, it was still a human body, one that was likely acquired illegally by the medical school. So the constable used his stick to remove the cloth and uncover the man's face.

---

It was John Scott Harrison, whom the family had just buried the day before. General Harrison probably shouldn't have paid the watchman in advance to guard the grave for 30 days.

John Harrison found a local undertaker to take custody of the body until he could figure out what to do, and he sent a telegram to General Harrison in Indianapolis, to let him know what had happened.

But by the time he received word from John, he had already heard the shocking news elsewhere. Three of his relatives who went to the cemetery to visit John Scott Harrison's grave earlier that morning were horrified to discover that the grave had been dug up, and the two smaller stones at the foot end of the casket had been lifted on end. There was a hole in the top of the vault, and the sealed casket had been pried open. After all the trouble General Harrison went through to ensure his father's eternal rest, his body had still be stolen.

Was one of the body snatchers present in the crowd at the burial? Had someone staked out the funeral to know what precautions were taken? This was a common practice for body snatchers, but removing the body through the foot end of the casket was not. Whoever stole the body obviously knew what they were dealing with ahead of time.

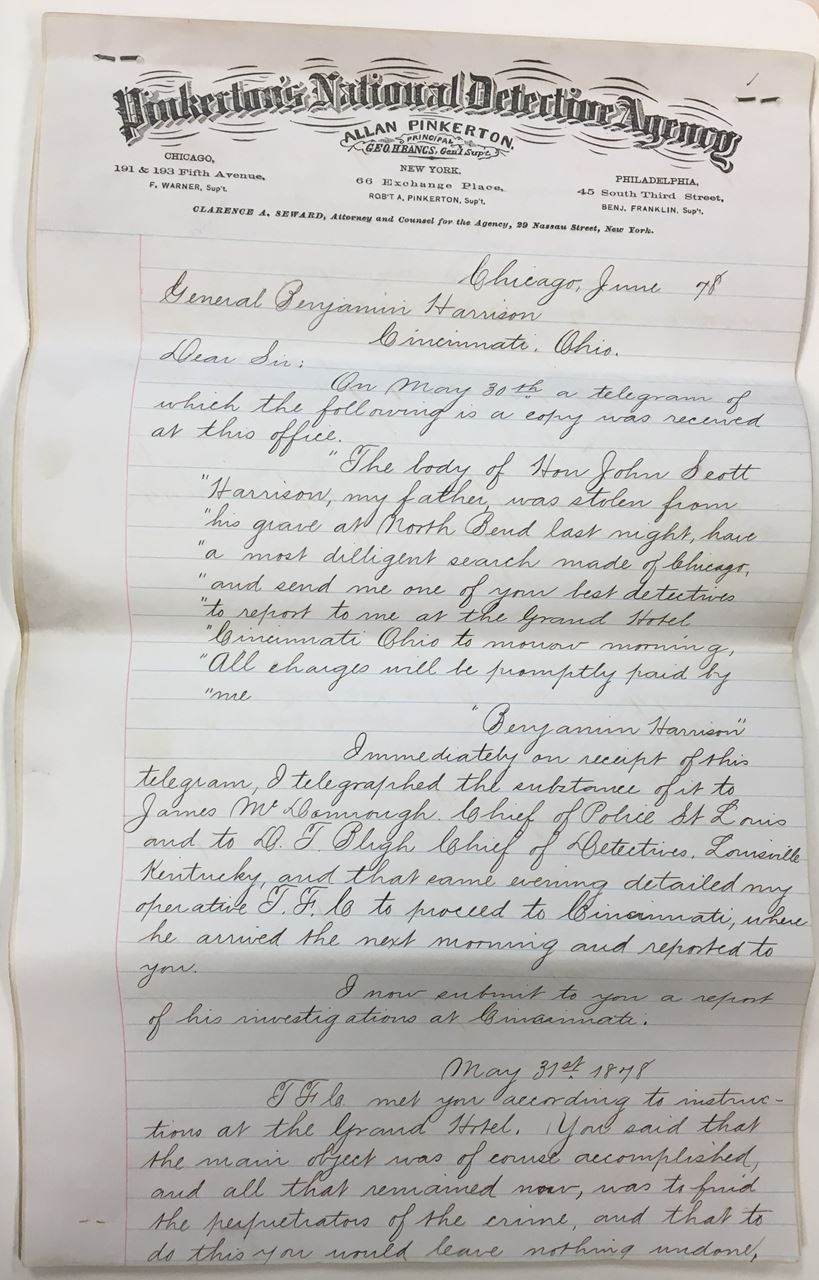

General Harrison immediately made arrangements to return to Cincinnati, thinking that he now had two bodies to locate. Right away, he met with the police, but he also hired the Pinkerton Detective Agency to find the culprits and track down the bodies. He wasn't messing around now, and he wasn't going to leave the whole case in the hands of the Cincinnati Police Department, who so far had not been very helpful. [Image: photograph of Pinkerton Detective Agency report on the Harrison body snatching, Benjamin Harrison Presidential Site]

General Harrison immediately made arrangements to return to Cincinnati, thinking that he now had two bodies to locate. Right away, he met with the police, but he also hired the Pinkerton Detective Agency to find the culprits and track down the bodies. He wasn't messing around now, and he wasn't going to leave the whole case in the hands of the Cincinnati Police Department, who so far had not been very helpful. [Image: photograph of Pinkerton Detective Agency report on the Harrison body snatching, Benjamin Harrison Presidential Site]

But with General Harrison back in town, the police now seemed more inclined to take action. They even made an arrest. Mr. Marshall, the janitor in the Ohio Medical College who had shown the constable and John Harrison around the building, was arrested and charged with "receiving, concealing, and secreting" John Scott Harrison's body which had been "unlawfully and maliciously removed from its grave."

This did not please the medical school staff, who all rallied around Mr. Marshall and posted his $5,000 bail.

This action by the medical school faculty did not please the good citizens of Cincinnati, who were a little creeped out by the medical school anyway and who were outraged by the body snatching that had been going on to supply it with bodies. It was shocking that the body of someone like John Scott Harrison might be treated so outrageously. And if it could happen to him, it could happen to anyone.

The medical school faculty, realizing that they were now even more firmly planted on the wrong side of public opinion, issued a statement expressing their "…deep regret that the grave of Honorable J. Scott Harrison had been violated" which is a pretty poor apology, I think. It's not really an apology at all.

One journalist reporting on the angry public reaction to this whole mess wrote of the medical school, "...it would have been better for it to say nothing at all... And heroic doses of the Ohio Penitentiary are the best medical treatment the people of Cincinnati can prescribe for it."

The Harrisons reburied their father and continued the search for Augustus Devin. Ohio Medical College faculty and staff were questioned again, this time before a grand jury. But they didn't have much to say, even under oath. A local journalist got a tip that a well-known and prolific body snatcher from Toledo, Ohio named Charles Morton and his gang of ghouls were responsible for both thefts. But no one could find him. He used several aliases, sometimes going by Gabriel Morton, or Dr. Christian, or Dr. Gordon.

Finally Ohio Medical College professors admitted to the grand jury what everyone already knew...that like most other medical schools in the country, theirs had entered into a contract with unnamed body snatchers to receive a regular supply of cadavers each year so that they had the "material" they needed to properly educate their students. These professors insisted, though, that they were as shocked as anyone else that none other than John Scott Harrison had turned up in their dissecting room. They were under the impression that private burials were not to be disturbed. Bodies were supposed to be coming from public burying grounds, or places where paupers or unclaimed bodies from hospitals and prisons, were buried…people they seemed to think mattered less.

These doctors who taught in these schools agreed that body snatching was a problem, but they also saw that it was a necessary evil. They felt sorry for the families and understood their anger, but they also supported the physicians who were driven to such means as purchasing bodies from body snatchers. It's tricky, isn't it? There were no imaging technologies, and the only way to better understand, and therefore better heal, the body was to look inside it and study it firsthand.

---

The janitor of another medical school in Cincinnati came forward confirming that they too purchased bodies from Morton. And he said that while school was not in session, Morton paid him to use the medical building as a workspace for preparing and shipping these bodies all over. Some of the bodies had gone to Ann Arbor, Michigan, disguised with labels that read "Quimby & Co.," so a detective set off right away to Ann Arbor. The barrels were easy to track, it turned out, and he quickly located a barrel labeled "Quimby & Co." Sure enough, inside that barrel of pickled bodies was....finally...poor Augustus Devin.

When the Harrisons in Cincinnati heard the news, they were quite relieved. Devin was laid to rest for the second time...for real this time. And though the whole business wasn't over...there was still an upcoming trial after all against Charles Morton and the janitor Mr. Marshall. And the Harrisons filed civil suits for the costs of the investigation and the pain and suffering caused by the whole terrible ordeal....But General Harrison could finally go home knowing that his father and Augustus were finally "home."