by Allison Reardon, Public History Graduate Student at the Indiana Medical History Museum

The history of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is extensive. In fact, it can be traced back to at least the Middle Ages [1]. Early descriptions of OCD-like symptoms are often connected to the idea of “scruples” [2]. According to Joanna Bourke in her article about religious scruples, people who suffered from it were in “a serious state of existence that included fanatical performance of religious devotion combined with an overwhelming burden of spiritual doubt” [3]. Several mentions of religious scruples can be found in sources from the 17th century, including a 1691 sermon from John Moore in which he labels scruples as “religious melancholy” [2]. This quote from Moore’s sermon is a perfect example:

overwhelming burden of spiritual doubt” [3]. Several mentions of religious scruples can be found in sources from the 17th century, including a 1691 sermon from John Moore in which he labels scruples as “religious melancholy” [2]. This quote from Moore’s sermon is a perfect example:

“Because it is not in the power of those disconsolate Christians, whom these bad Thoughts so vex and torment, with all their endeavors to stifle and suppress them. Nay often the more they struggle with them, the more they encrease [sic]” [4].

Along with these more general examples, there is evidence suggesting that some early religious figures suffered from scruples. One major figure, Martin Luther, who lived in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, is often cited as one of these “famous sufferers” [3]. An example of this scrupulous behavior is cited in a 2004 biography: “And yet my conscience would not give me any certainty, but I always doubted and said, ‘You didn’t do that right. You weren’t contrite enough. You left that out of your confession’” [5]. Although these religious obsessions would now be viewed as OCD-like symptoms, they were not always discussed in a psychiatric context. The shift to more psychiatric discussions occurred in the 20th century [3]. [Photo: Drawing based on a photograph of a person suffering from religious melancholy, printed in 1858.]

Moving past the narrow descriptions of scruples, the concept of OCD changed several times before eventually reaching our current definition of obsessions and compulsions. Even within the 19th century, psychiatrists differed in their definitions and understandings of the disorder. As mentioned on the Stanford Medicine website, “psychiatrists [mainly from France and Germany] disagreed about whether the source of OCD lay in disorders of the will, the emotions or the intellect” [2]. In the early 19th century, some psychiatrists, especially the French psychiatrist Esquirol, categorized the disorder under monomania, but by the end of the century, it was largely accepted as part of the broad category of neurasthenia [2]. (For more information about this diagnosis, check out this other blog post.)

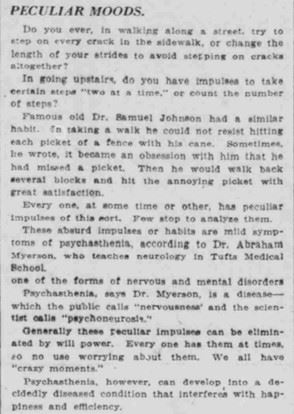

According to Stanford Medicine, OCD was more clearly distinguished from neurasthenia at the beginning of the 20th century by both Pierre Janel and Sigmund Freud [2]. In his 1920 book, A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis, Freud discusses “obsessional neurosis,” and he additionally credits both Janet and Josef Breuer with the discovery of “[t]he meaning of neurotic symptoms,” although he does express some disagreement with many of Janet’s views [6]. Janet proposed the isolation of “psychasthenia” from neurasthenia in Les Obsessions et la Psychasthenie (1903) [2]. Some other doctors of the time questioned his argument because they felt there was no reason to separate it from the already accepted diagnoses of neurasthenia and hysteria [7]. Despite this resistance, the term “psychasthenia” was used by some in early 20th century medical journals. [Photo: Part of a 1922 newspaper article describing symptoms of psychasthenia that are similar to possible symptoms of OCD]

additionally credits both Janet and Josef Breuer with the discovery of “[t]he meaning of neurotic symptoms,” although he does express some disagreement with many of Janet’s views [6]. Janet proposed the isolation of “psychasthenia” from neurasthenia in Les Obsessions et la Psychasthenie (1903) [2]. Some other doctors of the time questioned his argument because they felt there was no reason to separate it from the already accepted diagnoses of neurasthenia and hysteria [7]. Despite this resistance, the term “psychasthenia” was used by some in early 20th century medical journals. [Photo: Part of a 1922 newspaper article describing symptoms of psychasthenia that are similar to possible symptoms of OCD]

Psychasthenia was also an accepted diagnosis at Central State Hospital. The first mention of this specific diagnosis for a patient at Central State seems to have been in 1927, and between 1927 and 1946, 21 people were diagnosed with psychasthenia at their first admission to the hospital. Some of the diagnoses were listed as “psychasthenia or compulsive states,” which seems more closely related to the current name of the disorder [8]. It is difficult to tell how many people admitted to the hospital may have suffered with OCD before the name psychasthenia was used, but there are some broader diagnoses into which the disorder may have fallen. For example, “monomania,” “neurasthenia,” and general “psychoneuroses” were diagnoses that were used at the hospital before 1927 [9]. Although it is possible that people who received these diagnoses suffered with OCD, it is not possible to say that with certainty. Also, “religious excitement” is often listed as a cause for mental illness (as opposed to a form), even at the opening of the hospital, and it is possible that there is a connection to the idea of religious scruples [10]. Again, however, there is no way to prove this connection.

Eventually, people adopted the name “obsessive-compulsive disorder.” This label can be traced back to the German psychiatrist Westphal and the term “Zwangvorstellung” [2]. This term was translated into English in two different ways: “obsession” was used in Great Britain and “compulsion” in the United States [2]. A footnote in a 1952 printing of Freud’s A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis notes this difference. In this book, Freud describes “obsessional neurosis,” and the footnote explains that “Zwangneurose [is] sometimes called in English compulsion-neurosis” [6].

Although the name “obsessive-compulsive disorder” did not appear until well into the 20th century, the history makes it clear that it is not a new disorder. Examples of OCD-like symptoms have been present since at least the 17th century, and some are even cited before that time [2]. This history also illuminates the fact that there is always more to learn. In fact, part one of this series discussed the ongoing conversation among researchers about differences between OCPD and OCD [11]. Some recent research has also focused on the effects of trauma in OCD [12] (Interestingly, an article written during World War I discussed connections between psychasthenia and shell shock [13]). Overall, the history of OCD has been long and winding, and it is still a subject of learning and debate. The next part will focus on another aspect of this history: media representations.

References

[1] Baldridge, Iona C., and Nancy A. Piotrowski. “Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder.” In Magill’s Medical Guide, edited by Bryan C. Auday, Michael A. Buratovich, Geraldine F. Marrocco, and Paul Moglia, 1631-1634. 7th ed. 5 vols. Ipswich, MA: Salem Press, 2014.

[2] “History.” Stanford Medicine. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://med.stanford.edu/ocd/treatment/history.html.

[3] Bourke, Joanna. “Divine Madness: The Dilemma of Religious Scruples in Twentieth-Century America and Britain.” Journal of Social History 42, no. 3 (2009): 581-603. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27696480.

[4] Moore, John. Of religious melancholy a sermon preach’d before the Queen at White-Hall March the 6th, 1691/2 / by the Right Reverend Father in God John, Lord Bishop of Norwich. London: Printed for William Rogers, 1692; Ann Arbor: Text Creation Partnership. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/A51223.0001.001.

[5] Mullett, Michael A. Martin Luther. London: Routledge, 2004.

[6] Freud, Sigmund. A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis. Garden City, NY: Garden City Books, 1952.

[7] Schwab, Sidney I. “Psychasthenia: Its Clinical Entity Illustrated by a Case.” Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease 32, no. 11 (1905): 721-728, https://oce-ovid-com.proxy.ulib.uits.iu.edu/article/00005053-190511000-00003/HTML.

[8] Central State Hospital. (1927-1946). Annual Report of the Board of Trustees and Superintendent of the Central State Hospital at Indianapolis, Indiana.

[9] Indiana Hospital for the Insane. (1888). Annual Report of the Trustees and Superintendent of the Indiana Hospital for the Insane. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433004139758&view=1up&seq=9&skin=2021.

Central Indiana Hospital for the Insane. (1904). Annual Report of the Board of Trustees and Superintendent of the Central Indiana Hospital for Insane. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433004139766&view=1up&seq=9&skin=2021.

Central Indiana Hospital for the Insane. (1924). Annual Report for the Board of Trustees and Superintendent of Central Indiana Hospital for the Insane at Indianapolis, Indiana.

[10] Indiana Hospital for the Insane. (1849). Annual Report of the Commissioners and Medical Superintendent of the Hospital for the Insane, to the General Assembly, of the State of Indiana.

[11] Thamby, Abel, and Sumant Khanna. “The role of personality disorders in obsessive-compulsive disorder.” Indian Journal of Psychiatry 61, Suppl 1 (2019): S114-S118. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_526_18.

[12] Dykshoorn, Kristy L. “Trauma-related obsessive-compulsive disorder: a review.” Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine 2, no. 1 (2014): 517-528. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2014.905207.

[13] Williamson, R. T. “Remarks on the Treatment of Neurasthenia and Psychasthenia Following Shell Shock.” British Medical Journal 2, no. 2970 (1917): 713-715. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20308835.

Image Credits

Image 1: Bagg, W. ‘Religious melancholy’ after a photograph by H. W. Diamond. Drawing. Wellcome Collection. January 2, 1858. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/hu8xh2qs.

Image 2: “Peculiar Moods.” South Bend News-Times (South Bend, IN) 39, no. 194, July 13, 1922. https://newspapers.library.in.gov/?a=d&d=SBNT19220713.1.6&srpos=1&e=-------en-20--1---txIN-------.