by Norma Erickson

by Norma Erickson

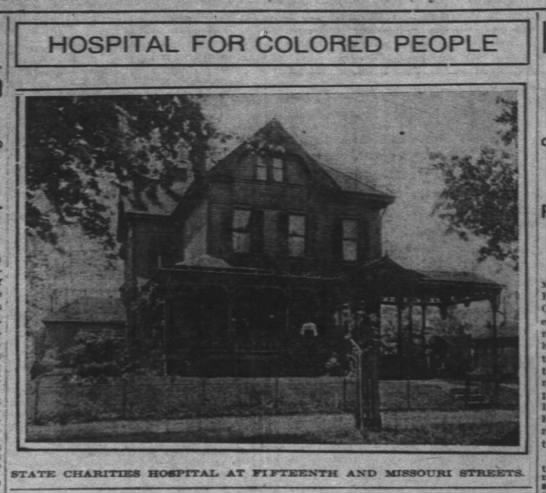

(photo: Sisters of Charity first hospital 'Hospital Indianapolis News, June 10, 1911)

When Vice president-elect Kamala Harris made her speech the night her running mate Joe Biden projected as the next President of the United States, she poignantly recognized “Women who fought and sacrificed so much for equality, liberty and justice for all, including the Black women, who are often, too often overlooked, but so often prove that they are the backbone of our democracy.” She confessed she stood on the shoulders of Black women who came before her , struggling to transform our nation from a society that derided and excluded people of color, to one that could, as a whole, become a better place when all were lifted to an equal standing. In the decades that surrounded the turn of the twentieth century, women of all races and even classes undertook an effort to improve society, approaching the problem from different value systems.

For white women who embraced the Progressive ideas of the time, their work became known as “municipal housekeeping”. Rooted in the idea of the woman was the mistress of her household domain, the existence of a healthy, well-ran home depended on a healthy, well-ran public sphere. They sought to “clean up City Hall” and improved many facets of life and work outside the home.

(photo: ad from The Freeman, January 25, 1913)

(photo: ad from The Freeman, January 25, 1913)

For some Black women, they were inspired by the Social Gospel Movement that recognized that Society—not just the Individual—required salvation. One historian framed black clubwomen’s motives as their desire to take control of their lives and to fulfill the Social Gospel through action, like the women who followed the historical Jesus of the New Testament. Social reforms became the vehicle for saving individuals, and by extension, the civic realm. As with the white push for change, the goals of Black women included uplift specifically for women. The marriage of these two manifestations of faith—uplift for salvation and female empowerment became important for many them.

Before going deeper in the health care history that involved these women, one misconception must be pointed out: Being Black in Indianapolis in the first decades of the twentieth century did not automatically mean you were poor. There might have been only one Madame C. J. Walker, the famous self-made millionaire, but there were many successful black businesswomen and wives of businessmen who lived a comfortable life and desired respectful treatment. Second, even working class women, many who were domestics, desired the same respect and were members of clubs that provided social interaction and improvement activities, including adequate and dignified healthcare. One example of their battle for respectability and the quest to improve lives stands out—the founding of a hospital for African Americans in 1911.

Several women’s clubs worked for improved healthcare in the African-American community of Indianapolis. Their efforts ranged from directly providing care, supporting the facilities, creating places for care, and training care givers. They undertook these projects with firm convictions that women possessed unique abilities that allowed them to carry out their missions of care and to do so with as much autonomy as possible. The most ambitious of these projects was the Sisters of Charity Hospital.

The Grand Body of the Sisters of Charity (GBSC), not to be confused with Catholic women’s religious orders with a similar name, was formed in Indianapolis in 1874 in response to the needs of large numbers of southern Blacks moving to the city near the end of the Reconstruction of the South that followed the end of the Civil War. Many women’s clubs formed for a variety of ends, some social or utility minded (for instance, sewing clubs) and some with for public goals in mind (one example is the Women’s Improvement Club). Many of them embraced the motto of the National Association of Colored Women: Lifting as We Climb. The GBSC differed slightly from other women’s clubs in that it operated as a lodge, with benefits to its members that satisfied needs like burial to financial assistance when needed. The underlying purpose of the hospital was to care for lodge members, but service was also extended to the entire Black community.

Originally housed in a former residence at 15th and Missouri Streets in 1911 (where the parking garage for the IU Health Neuroscience Center now stands), the hospital moved to another house at 502 California Street in 1918 (now an open lawn on the IUPUI campus. The hospital also served the community by formally training young women as nurses. This professional activity held great prospects for the advancement of Black women. They also worked with the juvenile courts and “wayward” girls. However much these services were sorely needed, such a small institution had a difficult time keeping up with necessary maintenance and improvements that would make the hospital a suitable place for surgery or a maternity hospital. Keep in mind that the Sisters of Charity Hospital and Lincoln Hospital were providing a place for care and treatment that should have been accessible to Black doctors, nurses, and patients as citizens and tax-payers of Indianapolis. It closed around 1921.

The Sisters of Charity pursued the quest for uplift for their community and briefly accomplished a unique achievement. The Sisters of Charity Hospital was a rare instance of an African American hospital owned and operated by black clubwomen in a northern state.

(photo: site of former SoCH at IU Health Neuroscience Center Garage 15th and Missouri, Google Maps 11-14-2020)