by Haley Brinker

by Haley Brinker

Snake oil. Those two words illicit an immediate response of fraudulent hucksters, traveling salesmen with dubious morals, and a host of other suspicious characters, hawking questionable wares across the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In modern times, calling someone a snake oil salesman is the equivalent of calling them a liar, a charlatan, peddling too-good-to-be-true products or ideas to make a quick buck. However, the history of snake oil itself is a little more interesting. Snake oil is and was a real product, and some scientists today acknowledge that it might actually work to cure bodily ills.

So, what is snake oil exactly? During the 1800s, over 100,000 Chinese immigrants came to the United States in order to find work building the Transcontinental Railroad. They brought with them their families, their culture, and, most important to this story, their medicines. One medicine, perhaps corked into a small, glass bottle, was snake oil. This was no ordinary snake oil, either. It came from the Chinese water snake, and this snake was rich [1]. No, not that kind of rich. The oil from Chinese water snakes is chock full of omega-3 acids. These have been known to help with things like arthritis and other muscle and joint pain [2]. The Chinese immigrants working on the railroad (all the live-long day) would have been exhausted and probably incredibly sore. The perfect cure? Snake oil! They might have even shared some with their fellow workers, building the miracle-cure aura of this product and spreading the news far and wide.

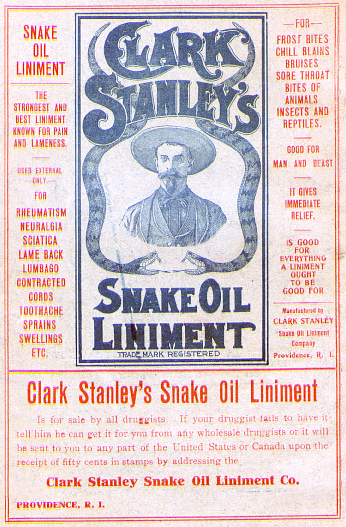

“But wait,” you say, “then why do people call snake oil fake?” That part comes next. Seizing on the newfound popularity of this miracle product, but lacking the ability to rustle up a Chinese water snake, the salesmen made do. Cue Clark Stanley, a Texan with panache and a scheme to get rich. Stanley called himself the “Rattlesnake King” and traveled across the United States, dressed as a cowboy, and put on shows [3]. In front of crowds, Stanley would slice open a live rattlesnake, throw it into boiling water, and bottle up the oil that rose to the top [1]. He claimed that this was what was in each bottle of “Stanley’s Snake Oil” and people lined up for a chance to buy it [3].

Unfortunately, shockingly, some cowboys just can’t be trusted, and Clark Stanley was a prime example of this. When the United States government decided to analyze the oil in 1917, they found that the Rattlesnake King’s oil was actually just a combination of mineral and fatty oils with a few additives, none of which derived from snakes [1]. They found him guilty of misrepresentation of his product and he was fined twenty dollars [2]. It’s worth noting that, even if Clark Stanley’s snake oil really did have genuine rattlesnake oil in it, it probably wouldn’t have been very effective. Modern studies have shown that the original snake oil from China, made from Chinese water snakes, contains around “20 percent eicosapentaenoic acid,” which is a type of omega-3. Rattlesnakes, on the other hand, only have a little over eight percent of the acid. It’s also worth noting that salmon, which is far easier to procure and much less dangerous to handle, have about eighteen percent [4]. Admittedly, though, Salmon King just doesn’t have the same ring to it.

After the Rattlesnake King’s treachery became public, it was only a matter of time before the term “snake oil salesman” became synonymous with fakes, frauds, and falsifiers. It was popularized when snake oil salesmen began popping up in American Westerns. It’s mentioned by the poet, Stephen Vincent Benet in John Brown’s Body and again in The Iceman Cometh by Eugene O’Neill [1]. These products of popular culture further propelled the terminology into the public lexicon. While snake oil itself (the good stuff from Chinese water snakes) is a great remedy in traditional Chinese culture, its benefits have been lost from sight in western culture, sinking beneath the surface of the slippery sea of slimy salesmen.

[1] Gandhi, L. (2013, August 26). A History Of 'Snake Oil Salesmen'. Retrieved September 24, 2020, from https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2013/08/26/215761377/a-history-of-snake-oil-salesmen

[2] Haynes, A. (2015, January 23). The history of snake oil. Retrieved September 24, 2020, from https://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/opinion/blogs/the-history-of-snake-oil/20067691.blog?firstPass=false

[3] Clark Stanley: The Original Snake Oil Salesman. (n.d.). Retrieved September 25, 2020, from https://ancientoriginsmagazine.com/clark-stanley

[4] Graber, C. (2007, November 01). Snake Oil Salesmen Were on to Something. Retrieved September 25, 2020, from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/snake-oil-salesmen-knew-something/

Photo Credit: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/ephemera/medshow.html, attributed to: Clark Stanley's Snake Oil Liniment, True Life in the Far West, 200 page pamphlet, illus., Worcester, Massachusetts, c. 1905