by Norma Erickson

It’s sometimes difficult to grasp why racial health disparities still exist in the twenty-first century. There are many aspects to the problem. One that is very relatable to everyone today is …money. How is healthcare paid for and who pays for it?

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, there were few choices. Starting with the most expensive, the very rich were cared for in their homes. Their physician made house calls and private duty nurses provided round-the-clock care. If one had the means, a private sanitarium (a for-profit hospital typically owned by one doctor, sometimes a group of them) cared for patients in need of surgery or other higher level care. If you had a little money, the public or municipal hospital offered affordable care for paying patients and the patient’s own doctor could still have charge of their case.

The public hospital also admitted the poor, whose care fell to the hospital staff physicians. In the case of a municipal hospitals with connections to medical colleges, interns and student nurses gave care under the guidance of professional staff (Indianapolis City Hospital for instance). For minor care and medications, the very poor could access publically funded dispensaries; again, these often doubled as teaching sites.

At the end of the Civil War, most of the nation’s African American population lived in the South, existing in an agriculture-based economy that placed no expectations on education. Eventually, many would leave to find better opportunities in the North’s large cities. Indianapolis was a very interesting northern city because, unlike some the larger metropolitan areas, its African American population grew at a relatively slow pace. This allowed the white population to become more familiar with their new neighbors and the establishment of businesses and occupations that crossed over the color line, a line of social segregation between the races that stood solidly until the latter years of the twentieth century.

The Black community developed class strata, just as did the white side. There were well-to do folks, a hardworking middling group, laborers, and the indigent on both sides. On the Black side of the line, no matter the group, an underlying missing element—that most of the white side enjoyed as a given—was respect. African Americans could find that respect within their own environment, but truly adequate healthcare existed only on the other side of the line, where respect was hard to gain. For many in the middle group (small business owners, craftspeople, high-level service workers like train porters), the public hospital was the only option, and they knew that even if they paid, they would be admitted to the worst section of an aging building without access to their own doctor and at the mercy of a staff that might not respect them.

The leaders in the Black community understood that the providing and receiving healthcare was an economic issue. The community was missing out on opportunities for employment (nurses and developing technology specialists) and higher level physician skills with required modern surgical equipment and support.

Except for the Alpha Home for Women that cared for aged black women, no institutional medical facilities for Blacks existed in the city until the 1896 when a new physician, Fernando Beamouth, opened a sanitarium at 651 North Senate Avenue. The Freeman, a major Black newspaper, noted that this was the first sanitarium in the state for Black patients and only the second in the nation to be started by doctor of color. Beamouth died in 1897. In August 1903, several prominent men in the Black community, including Dr. Sumner Furniss, tried to purchase a building in the 900 block of North Meridian to start a clinic, but abandoned the project when white neighbors objected.

Later, Dr. Joseph H. Ward opened his sanitarium on Indiana Avenue around 1906 (the actual date is unclear). This first viable effort mostly served the portion of the population able to pay for private care. For the first few years, Ward did not advertise his sanitarium in the newspapers, but the society pages occasionally announced hospitalizations there, naming patients known as elite members of the black community. Later, he was Madame C.J. Walker’s personal physician. It is likely he also cared for a few charity patients, too.

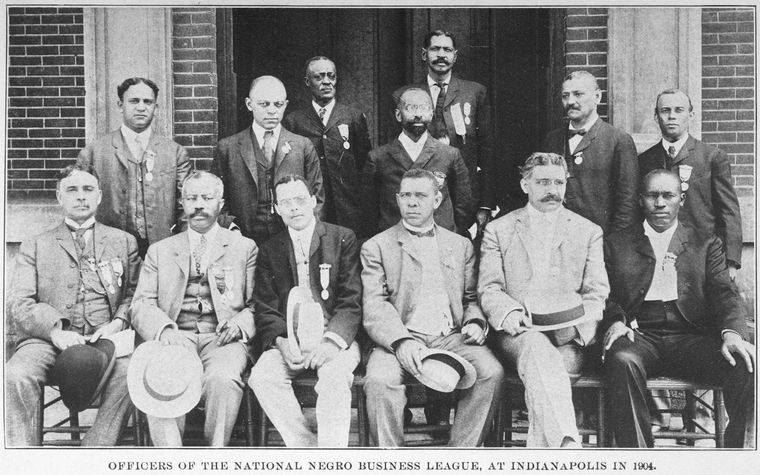

Beamouth, Ward, and Furniss were also members of the Black business league. Ward acted on the fuller economic function of health care as a source of good-paying jobs by starting a nurse training program. His sanitarium filled a gap for the elite, but the middle class needed an alternative to the City Hospital. In 1909, Furniss and several other Black doctors formed the Lincoln Hospital that would function as a public hospital for the African American community with the ability to pay for care. The Lincoln Hospital and its physicians will be the subject of the blog post next month in The Struggle for Adequate Healthcare for African Americans in Indianapolis-1906-1925 Part III.

Photo: Officers of the National Negro Business League, at Indianapolis in 1904 from the collection of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library. Dr. Sumner Furniss is the first on the left in the second row.