by Allison Reardon, IMHM Public History Graduate Intern from the Indiana Medical History Museum

From TV shows like Monk to movies like As Good As It Gets, we commonly see obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) portrayed in pop culture. However, it is not always portrayed accurately, and this can cause real harm to people living with the disorder. For some people, media representations may be the first way they learn about OCD and the people affected by it. If these portrayals are inaccurate and promote stereotypes, they can contribute to the stigma around mental illness that often stops people from seeking help or talking about their struggles [1]. Therefore, it is important to assess OCD in media and the ways in which people’s perceptions of the disorder may be influenced.

OCD has not always been portrayed in the same way throughout history. In his article “What’s So Funny about Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder?,” Paul Cefalu explains that more recent characters suffering from OCD are “typically cast [...] as the protagonists in comedies,” but earlier depictions “often showed up in melodramas, tragedies, and gothic literature” [2]. As discussed in part two of this blog post series and mentioned by Cefalu, these earlier depictions were not clearly labeled as OCD and were, instead, viewed as diagnoses like monomania and scrupulosity [2]. Because of these differing diagnoses, it is sometimes difficult to clearly identify the characters as people dealing with OCD. However, obsessions and compulsions are common symptoms in many of these gothic stories.

Many of Edgar Allan Poe’s stories involve monomania. However, several modern diagnoses would have fallen into the category of monomania, with one article describing paranoid schizophrenia in “The Tell-Tale Heart” and phobias in “The Premature Burial” [3]. OCD would have also fallen into this broad category. Although the characters in these monomania stories are often associated with different modern diagnoses, it is useful to discuss them in the context of OCD because they would have been perceived similarly at the time. [Photo: 1935 illustration by Arthur Rackman for Poe’s short story “The Imp of the Perverse.”]

Although the characters in these monomania stories are often associated with different modern diagnoses, it is useful to discuss them in the context of OCD because they would have been perceived similarly at the time. [Photo: 1935 illustration by Arthur Rackman for Poe’s short story “The Imp of the Perverse.”]

One thing that stands out in these gothic stories is the violence often carried out by characters with monomania. For example, one story by Poe that is often cited as an example of intrusive thoughts, which play a significant role in OCD, is “The Imp of the Perverse” [4]. In this story, the narrator’s intrusive thoughts lead him to kill another person. Violent representations like this example contribute to stigma and prejudice surrounding mental illness [1]. Also, it is an inaccurate representation of obsessive-compulsive disorder because according to OCD-UK, “people living with OCD are the least likely people to actually act on such thoughts” [5].

In more recent times, media representations of OCD have moved away from these violent depictions to more comedic portrayals. However, these can still be harmful. As described by Paul Cefalu, “mainstream depictions tend to make us forget that, according to the DSM IV, OCD is fundamentally an anxiety disorder, hardly a laughing matter to most of its long-term victims” [2].

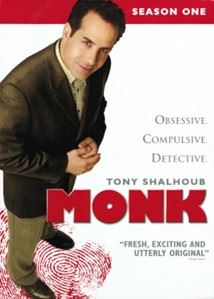

A 2018 study delved into one particular comedic portrayal of the disorder: Monk. The title character, Adrian Monk, suffers from OCD, and the show has received a lot of praise and acclaim for this representation. However, this particular study, which focused on reception of the show from people dealing with OCD and other anxiety disorders, demonstrated that there were some negative reactions to it. For example, one person responded to the show by saying that it “minimizes the suffering of a person with severe OCD experiences [because it] tends to feed the stereotype that OCD is merely about fear of dirt and germs.” Another person responded by explaining that although “the humor on the show lightens up the topic of mental illness,” it also “makes light of being mentally ill in a society that already thinks we are dangerous/completely crazy/the butt end of all jokes and useless to society” [6]. [Photo: Monk Season 1 DVD cover, which describes the title character with the words “Obsessive. Compulsive. Detective.”]

A 2018 study delved into one particular comedic portrayal of the disorder: Monk. The title character, Adrian Monk, suffers from OCD, and the show has received a lot of praise and acclaim for this representation. However, this particular study, which focused on reception of the show from people dealing with OCD and other anxiety disorders, demonstrated that there were some negative reactions to it. For example, one person responded to the show by saying that it “minimizes the suffering of a person with severe OCD experiences [because it] tends to feed the stereotype that OCD is merely about fear of dirt and germs.” Another person responded by explaining that although “the humor on the show lightens up the topic of mental illness,” it also “makes light of being mentally ill in a society that already thinks we are dangerous/completely crazy/the butt end of all jokes and useless to society” [6]. [Photo: Monk Season 1 DVD cover, which describes the title character with the words “Obsessive. Compulsive. Detective.”]

Although many pieces of media depict OCD in a comedic way that contributes to stigma and stereotyping, not all recent portrayals are harmful. In fact, one more accurate representation is found in a book that conveniently has a strong Indiana connection: Turtles All the Way Down by John Green. The main character of this Indianapolis-based book, Aza Holmes, suffers from OCD, and this portrayal is largely informed by Green’s own experiences with the disorder. Because of this basis in reality, the book gets a lot right about the disorder, those struggling with it, and people trying to support loved ones with OCD. In the article “How ‘Turtles All the Way Down’ Perfectly Explained My OCD,” Maia Kinney-Petrucha explains her connection to the story through this statement: “It felt like I experienced something more than empathy” [7]. Another article discusses the book’s portrayal of mental illness and ultimately praises it and recommends that it “be used in secondary English classrooms to create mental health allies” and to provide accurate representations for young adults struggling with OCD [8]. [Photo: Book cover for Turtles All the Way Down by John Green.]

Overall, media representations of OCD have rarely been completely accurate. As one article explains, it is important to be aware of the impact of these portrayals, especially in “depictions of stigmatized groups that are tinged with humor, where there is a fine line between what can seem true and what can seem trivializing” [6]. Although there are positives associated with the depiction of OCD in pop culture, we still have a long way to go to accurately depict the disorder and reduce stigma around it. As mentioned by Rachel May in an article discussing OCD in Encanto, “[a]t a time when anxiety disorders (of which OCD is a part) and depression are skyrocketing among both children and adults due to the pandemic, it would be helpful to see OCD accurately represented, and to use a mentally ill character for something other than the punchline” [9]. The next part of this series will focus on COVID-19 and some of the unique challenges of OCD in the pandemic, demonstrating the need for more accurate media portrayals.

especially in “depictions of stigmatized groups that are tinged with humor, where there is a fine line between what can seem true and what can seem trivializing” [6]. Although there are positives associated with the depiction of OCD in pop culture, we still have a long way to go to accurately depict the disorder and reduce stigma around it. As mentioned by Rachel May in an article discussing OCD in Encanto, “[a]t a time when anxiety disorders (of which OCD is a part) and depression are skyrocketing among both children and adults due to the pandemic, it would be helpful to see OCD accurately represented, and to use a mentally ill character for something other than the punchline” [9]. The next part of this series will focus on COVID-19 and some of the unique challenges of OCD in the pandemic, demonstrating the need for more accurate media portrayals.

References

[1] “Stigma, Prejudice and Discrimination Against People with Mental Illness.” American Psychiatric Association. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/stigma-and-discrimination.

[2] Cefalu, Paul. “What’s So Funny about Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder?” PMLA 124, no. 1 (2009): 44-58. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25614247.

[3] Zimmerman, Brett. “Poe as Amateur Psychologist: Flooding, Phobias, Psychosomatics, and ‘The Premature Burial.’” Edgar Allan Poe Review 10, no. 1 (2009): 7-19. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41507855.

[4] Mahoney, Donna M., and Deborah L. Wilke. “The Self Psychological View of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Treating the Tormented Self.” Annals of Psychotherapy & Integrative Health (Spring 2012): 26-34.

[5] “What are obsessions?” OCD-UK. Accessed January 29, 2022. https://www.ocduk.org/ocd/obsessions/.

[6] Hoffner, Cynthia A., and Elizabeth L. Cohen. “A Comedic Entertainment Portrayal of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Responses by Individuals With Anxiety Disorders.” Stigma and Health 3, no. 2 (2018): 159-169. http://dx.doi.org.proxy.ulib.uits.iu.edu/10.1037/sah0000083.

[7] Kinney-Petrucha, Maia. “How ‘Turtles All the Way Down’ Perfectly Explained My OCD.” The Mighty, November 26, 2017, https://themighty.com/2017/11/turtles-all-the-way-down-john-green-explain-obsessive-compulsive-disorder-ocd/.

[8] Hall, Michael. “Bibliotherapy and OCD: The Case of Turtles All the Way Down by John Green (2017).” New Horizons in English Studies 5, no. 1 (2020): 74-87. doi: 10.17951/nh.2020.5.74-87.

[9] May, Rachel. “Let’s Talk About Bruno: In Encanto’s OCD Allegory, the Weird Brother Deserves Better.” Literary Hub, January 26, 2022, https://lithub.com/lets-talk-about-bruno-in-encantos-ocd-allegory-the-weird-brother-deserves-better/#top.

Image Credits

Image 1: Rackman, Arthur. Illustration for “The Imp of the Perverse.” In Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination. 1935. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:09_rackham_poe_impoftheperverse.jpg.

Image 2: “Monk Season One DVD.” Wikimedia Commons. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Monk_Season_One_DVD.jpg.

Image 3: “John Green Turtles All the Way Down Book Cover.” Wikimedia Commons. https://en.wikipedia.